Safe foods in Mbeya’s markets: inclusion is a must.

In just a decade, the population of Mbeya has grown from 385,279 to 620,000 inhabitants according to the 2022 national census. However, the city’s urban infrastructure is struggling to keep pace with this rapid growth. With such an influx of people, ensuring that everyone, especially the most vulnerable citizens, has access to safe and nutritious food becomes more urgent every day. Find out how Rikolto and its partners are starting to drive collaborative change in the city’s public market.

Soweto Market in Mbeya. Picture by Lisa De Vos, Rikolto.

In 2021, Rikolto conducted a study on the contamination levels of fruit and vegetables in several public markets in the Southern Highlands of Tanzania. The study found biological contaminants such as E. coli, S. aureus, and Salmonella, and lead levels five times higher than recommended standards in various foods. While these results shed light on the many food safety risks, we know it is only one side of the coin.

The risks of food contamination are everywhere. So, mainstreaming good food safety practices requires a change from the production and distribution level to local and national policies that regulate and incentivise these practices.

Safe and nutritious food in a changing climate.

The global numbers of foodborne illnesses and deaths due to contaminated food continue to be alarming. Moreover, the evidence of the link between nutrition and food safety is clear. We may eat nutrient-rich vegetables, but they may be contaminated at the market due to the inferior quality of the water used to clean them. Healthy food is both nutritious and safe to eat.

Now let us consider the added impact of climate change. Excessive rainfall can damage or spoil crops, droughts affect irrigation water quality, and high temperatures increase pest populations, potentially leading smallholder farmers to rely more on agrochemicals. Changes in temperature can also prompt farmers to switch crops, impacting food security.

A multitude of factors, actors, and interactions need to be addressed and harmonised to ensure access to safe and nutritious food for urban dwellers.

Getting everyone around the same table

In, 2020, Rikolto helped create the Mbeya Food Smart City Platform, known in Swahili as Jukwaa la Usalama wa Chakula Mbeya.

Established with the Tanzania Chamber of Commerce, Industry, and Agriculture (TCCIA) and the Mbeya City Council (MCC), the platform gathers NGOs, agrifood businesses, government departments, and farmers’ associations.

Meeting of the Mbeya Food Smart City Platform.

This multi-stakeholder process, supported by the AGRI-CONNECT programme funded by the European Union, is facilitating shared understanding, dialogue, and coordination to address Mbeya’s food system challenges, including food safety.

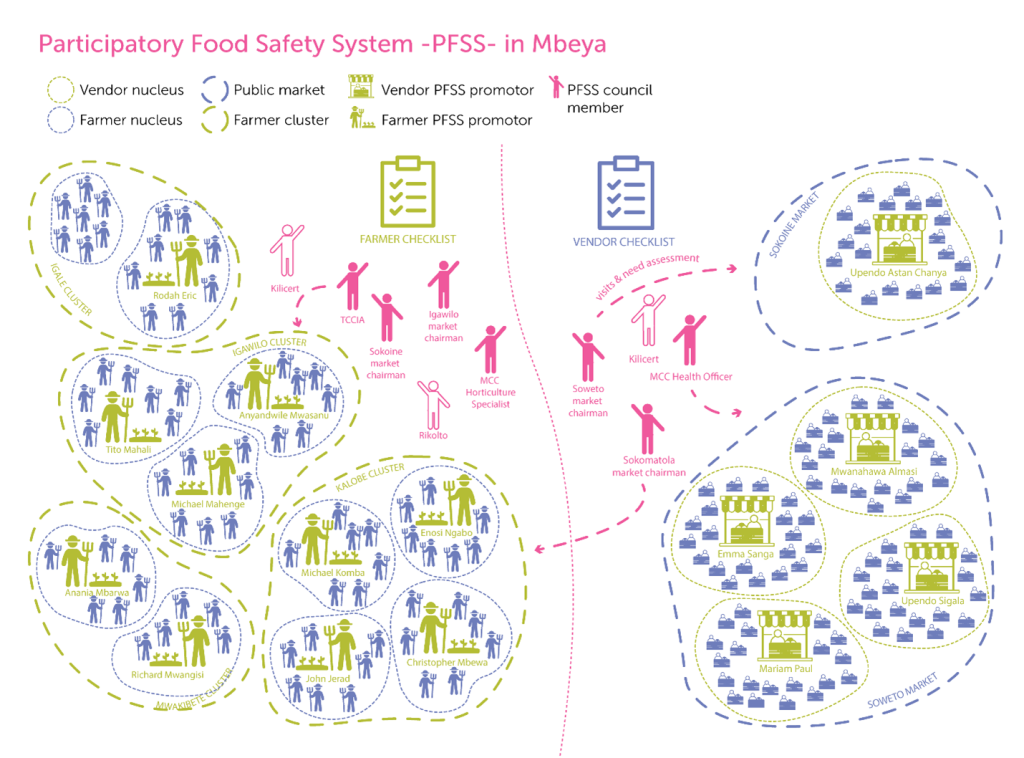

Building on the platform’s strategy, in 2023 Rikolto and its partners launched a pilot for an adapted participatory guarantee system to ensure safe fresh fruit and vegetables in the traditional markets of Soweto and Sokoine.

Multi-stakeholder and territorial coordination

Rikolto enable inclusive conversations to ensure that any process of change in practices or policy frameworks includes the often-marginalised voices, such as smallholder farmers, women, informal workers, and young people. Our work to promote multi-stakeholder coordination in the Mbeya Food Smart City Platform to address food safety from production to food handling, is a step towards a more sustainable food system transformation. Learn more about our Sustainable Food Systems approach

Designing a tailored system

A participatory guarantee system, or PGS, is a mutual validation system where farmers, consumers, and other city or local authorities check their peers and themselves to guarantee food quality. This avoids an expensive third-party control system. It has many advantages such as: its participatory approach, it is less costly, it reduces the administrative burden, and it is designed to build capacity among stakeholders along with mutual trust.

What makes this model different from other participatory guarantee systems for organic farming, is the focus on safe production and food handling. Rikolto and partners refer to it as a Participatory Food Safety System (PFSS).This adapted system of the global GAP standard not only looks at on-farm practices but involves actors and practices along the entire value chain.

Traditional markets are the first point of access to food for the majority of Tanzanian citizens; therefore, market vendors are crucial participants in the system.

The process is based on peer review and learning. Farmers and market vendors evaluate their food safety practices using a checklist, which is reviewed and assessed on the farm and at the market stall.

The pilot involved farmers from Kalobe, Igawilo, Mwakibete, and Igale clusters, market vendors from Soweto and Sokoine markets, and platform members including the Mbeya City Council’s (MCC), TCCIA, and food safety expert Kilicert. The training was conducted using the training of trainers (ToT) model, where trained farmer and vendor leaders would train their peers.

Members of the Platform’s food safety and hygiene sub-committee took on the role of the council to follow up on the pilot, along with Rikolto and other stakeholders. They also received training on the PFSS.

The process was aligned with the fruit and vegetable harvest cycles. A four-month experimental phase was agreed upon, between September 2022 and March 2023, with a plan for a six-month cycle once the system is more established. By the end of the first project cycle, ten nuclei of farmers and five of vendors were created.

Nuclei were established to facilitate training, evaluations, and internal visits between participants, with each farmer leader coordinating a nucleus of up to 8 members, and each market vendor leader coordinating a nucleus of up to 12 members – PFSS pilot diagram by Lisa De Vos.

The brand and logo “Chakula Bora-Safi Na Salama” were designed in a participatory way to encourage a sense of belonging among participants and to identify produce assessed in the PFSS within the market.

The pilot operates under the assumption that consumers will be more interested in safe produce if it is available at the same price as regular produce. If consumers end up choosing safer produce, this would mean a potential increase in sales and higher incomes for farmers and vendors. Apart from the moral commitment to providing healthy food, this serves as an incentive for them to participate in the PFSS.

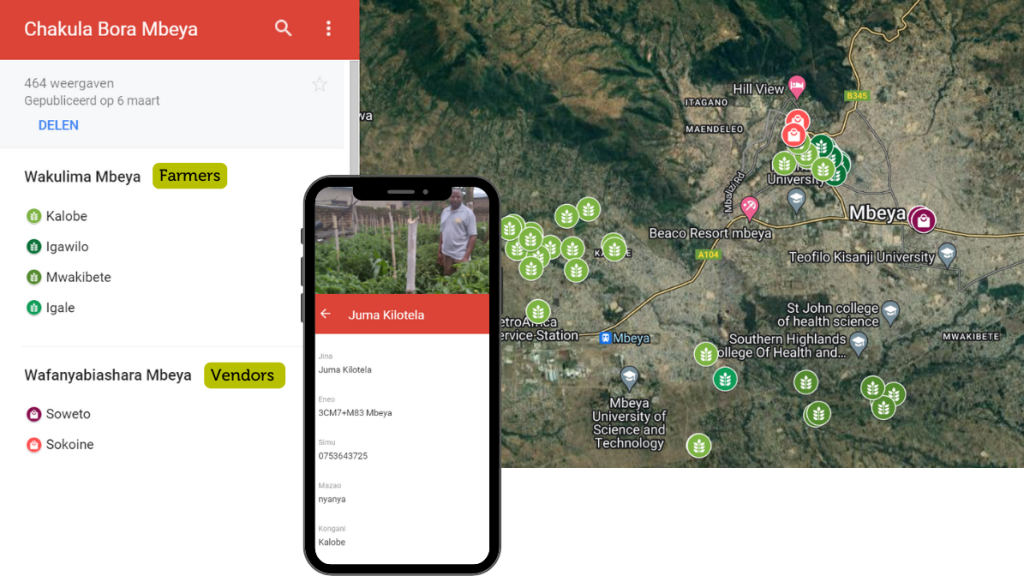

To further strengthen the visibility of the initiative and to improve internal communication among the participants, an online map was developed.

With a specific logo and an online database, a solid foundation was put in place to stimulate market access for PFSS products and to connect farmers and vendors to create local safe value chains.

“In the last two years, I have worked with the vendors from the Soweto market I have seen how their participation in the platform and various food safety activities have changed in the market area. They have started wearing working coats, cleaning the market environment but also communicating with various city departments about market services such as waste collection and enforcement of bylaws.” – Lilian Mbilinyi, Mbeya Food Smart City Platform coordinator for TCCIA.

Achievements and challenges

As the PFSS initiative in Tanzania takes its first steps, Rikolto and its partners have already gained valuable insights from the initial cycle. Drawing from these successes and challenges, we are working on the second cycle in Mbeya:

- Effective teamwork and communication – The involvement of multiple stakeholders, especially our food safety champions, played a key role in fostering a common understanding of PFSS among the participants. The food safety champions were Lilian Mbilinyi of TCCIA and Barack Kipesha, the Mbeya Town Health Officer. They led the assessment and improvement of the PFSS tools and procedures. They visited farmers and vendors to learn about the barriers and advantages they were facing and their progress. To further this, farmers and vendors were closely supported at every step and in the use of the tools by the iCRA, MIICO, and TCCIA networks.

“By making sure everyone is on board on PFSS, we succeeded in completing all the steps of the PFSS cycle within one harvest season and adopting a practical approach to problem-solving or system setup ambiguities observed by different actors.” Lisa De Vos, project coordinator of Rikolto.

Exchanging experiences among cities – Rikolto is also implementing a Participatory Food Safety System (PFSS) pilot in Arusha, 15.5 hours from Mbeya. This is a joint effort with the City Council and a multi-stakeholder platform. To promote cross-learning between the cities, the PFSS pilots were launched simultaneously. Concretely, we organised a learning exchange between partners in Mbeya and Arusha. As a result, the Rikolto and TCCIA teams formed a partnership for the PFSS pilot in Arusha, inspired by the success in Mbeya. This is a promising step towards building local capacity, sustainability, and expansion of PFSS to new cities in the future.

Furthermore, in Arusha, while the first cycle is still underway, our friends at Iles De Paix (IDP) and the regional farmers’ umbrella organisation MVIWAARUSHA have joined forces enthusiastically under our “Chakula Bora-Safi Na Salama” logo.

Arusha central market. Picture by Thomas Kuyper/ Iles De Paix (IDP)

- Relevance of context-specific tools – A participatory system relies on all participants understanding the process and having access to the necessary tools. The primary tool for PFSS is a checklist used throughout the verification process. While not all farmers and vendors have digital know-how, the PFSS pilot works with hard copies of the list, kept in one office for systematisation. However, this made it difficult for participants to access the data, review comments and learn. It also showed that it is important to test the checklist with many different users such as farmers, vendors, but also PFSS council members.

- Long-term viability of the PFSS depends on cost coverage by participants – PFSS can only be sustained if the participants can cover the costs. This requires controlling costs and offering enough value to consider it a profitable investment. As part of the lessons learned from the first cycle, we are also raising the idea among platform members of seeking funding to help TCCIA continue its role as implementer and champion beyond the current pilot.

“We have made a preliminary calculation of the average market price of PFSS produce for this first cycle, focusing primarily on human resources. We will make a second calculation in the second phase, and we expect to have a full cost of the model after the third cycle.” – Shukuru Tweve, project coordinator of Rikolto

- Capacity building beyond farmers and vendors for mitigating food risks – The pilot highlighted the challenge of farmers and vendors lacking the capacity to mitigate all food risks in their area of intervention. Challenges like clean water access and hygienic environments are difficult to capture in the PFSS checklist and may bias the results. A follow-up plan and engagement with the municipality is underway within the platform to encourage infrastructure investments.

- Establishing a strong safe food logo – Ideally, the “Chakula Bora-Safi Na Salama” logo should be recognised as an official certification standard by the local government authorities and approved by the Tanzania Bureau of Standards (TBS). However, it is being supported by the government authorities through the involvement of city officials in the PFSS Council. The TBS has also suggested that it be involved in future food safety training. This official support would enhance the credibility of the logo. At the moment Rikolto is ‘running’ the logo. We have begun conversations to explore whether this could be transferred to the multistakeholder platforms in both cities.

- Overcoming seasonal farming and land tenure challenges – If you are not sure that you will be able to continue farming on the same land, how can you invest in safer practices and the land environment? Addressing these obstacles can encourage long-term commitment and adoption of safe farming methods.

Next steps

Looking ahead to the next phase, Rikolto, and its partners are already identifying synergies and improvements to the system. This involves addressing the following topics:

- The journey from field to plate often involves more actors than farmers and vendors. To address these steps, we are developing a strategy to engage transporters in PFSS together with our partners from MIICO.

- To improve data management, a clear recording system should be set up from the beginning of each cycle, with designated responsible persons to maintain it. Rikolto and its partners are exploring investing in capacity building to use Kobo, a data collection tool.

- TCCIA is taking the lead in assessing the checklists and manuals together with the PFSS participants. Kilicert will assist in updating these tools and training to be even more context-specific and user-friendly for all participants. In this way, we aim to increase the number of farmers, vendors, and other value chain actors that can participate in the system!

- We will create an accessible platform for the “Chakula Bora-Safi Na Salama” map to create online visibility. Combining this with visibility for the logo in the markets of Soweto and Sokoine and consumer sensitization campaigns on food safety and nutrition from TCCIA and MIICO, we aim to show consumers they can have secure access to safe fresh fruit and vegetables in Mbeya.

This post is produced with the financial support from the European Union through AGRI-CONNECT Programme. Its contents do not necessarily reflect the views of the European Union.

This article is republished from RIKOLTO website. Read original article.